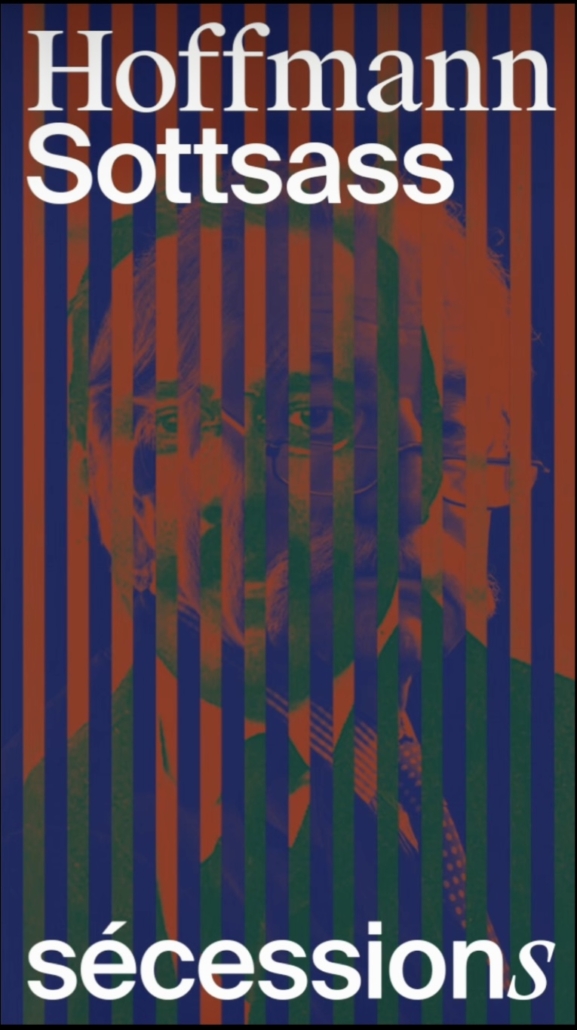

Josef Hoffmann / Ettore Sottsass

Sécessions

By exhibiting around forty exceptional pieces by Josef Hoffmann and Ettore Sottsass, Romain Morandi has chosen to confront two major figures in the history of architecture and design. While Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) is considered one of the fathers of the modern movement, Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007) was one of the first to question its foundations. There is, however, a deep link and a true filiation between these two creators of genius: it was driven by the same refusal of academicism that Sottsass undertook, at the turn of the 1950s, a long work of deconstruction of the principles erected by Hoffmann at the end of the 19th century. Where Hoffmann spoke out against official salon art, Sottsass rejects the impoverished language of a modernism locked in its own codes. Half a century apart, both, in their own way, decided to “secession”, turning the history of design and decorative arts upside down.

In 1896, upon leaving the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he was a student of the great architect Otto Wagner (like Ettore Sottssas’ father), Josef Hoffmann spent a year in Italy. On his return he founded La Sécession with Josef Maria Olbrich, an association of artists and architects whose objective is to bring together and renew the applied arts by creating a total art (Gesamkunstwerk). They thus intend to develop a new form of artistic expression that is “spiritual, modern and authentic” applied to all fields of creation.

“Our art is not a fight of modern artists against the ancients, but the promotion of the arts against peddlers who pose as artists and who have a commercial interest in not letting art flourish. Commerce or art, this is the issue of our Secession. It is not a question of an aesthetic debate, but of a confrontation between two states of mind“, we can read in the first issue of the magazine Ver Sacrum, official organ for disseminating the Secession as a Manifesto.

More than half a century later, the actors and the issues have changed but the deep conviction of Ettore Sottsass remains the same: it is not a question of refusing the part of heritage inherent in any creative act but of defending the idea that art and creation have a role and a power to transform society.

Although his first creations were anchored in a grammar inherited from the modern movement, Sottsass gradually made a stylistic shift. It was during the 1960s and 1970s that he laid the foundations of his formal vocabulary, which led him, at the beginning of the 1970s, to join the Anti-Design movement, the slayer of consumerism and mass production. It is in this perspective that the famous exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” was held in 1972 at the MoMA in New York which brought together, in addition to his production, works by Mario Bellini, Joe Colombo, Ugo La Pietra, Gaetano Pesce or Superstudio.

For Josef Hoffmann, an object must be “aesthetically beautiful” but also “morally good”. its quality does not reside only in the work of the artist’s hand, it is also expressed in the clarity of the formal expression and the integrity of the workmanship. According to him, “under certain conditions a reasonable mass-produced item can be created using machines, but it must nevertheless unconditionally bear the imprint of workmanship.” He worked closely with Gustav Siegel, one of his former students, who headed the workshops of the Jacob and Josef Khon company, which gradually established itself as one of the leading furniture manufacturers in Austria -Hungary. Hoffmann also uses certain models imagined by Siegel in his projects, blurring the boundaries of their collaboration. Together they will participate in forging the creator-editor couple, thus contributing to the advent of design in its current sense. The “Sitzmachine” armchair (Literally “Machine for sitting”) presented for the first time at the Milan Fair in April 1906 constitutes one of the most striking examples of the collaboration between Josef Hoffmann and J&J Kohn.

From the start of his career, Ettore Sottsass has also always worked jointly with artisans, allowing him to continue his work of experimentation on shapes and materials. From his friendship with Aldo Londi, the artistic director of Bitossi e Figli, an extremely sophisticated production was born; Sottsass revisits traditional Tuscan ceramics with more modern decorative motifs, covered with metallic oxides, platinum or lava. With the jeweler Gem from Milan, he offers pieces combining lapis lazuli, coral or turquoise with gold. Finally, with the cabinetmakers from Poltronova, he combines ceramic, aluminum or lacquer with traditional walnut. The Italian architect’s impressive production is always the result of a close relationship and deep respect between the creator and his publisher.

Whatever the field of intervention (architecture, furniture, lighting, fire arts, textiles, brassware), the aesthetic defined by Josef Hoffmann is based on a geometric ideal. Described as “proto-cubist”, his creations open, through their purity, the path to functionalism. From the end of the 19th century, Hoffmann developed a system based on the line, the square, the circle and their volumetric variation, the cube, the block or the sphere. The line finds materiality in the bars of the chairs, tables or benches. We find the circle in the work of curved wood, which gives sensuality to the most voluminous seats and facilitates their integration into the space. The only concession made to the ornament, if it did not participate in the structure of the object, the sphere intervenes as a punctuation. The square emphasizes the synthetic character of both the furniture and the architecture. Worked in pattern, its repetition in solids or voids allows to structure the composition of the objects.

Far from refusing the Viennese aesthetic heritage, Sottsass appropriates it and revisits its key elements. It was during his collaboration with Poltronova (1958-1974) that he developed his own formal language. He abandons the organic forms dear to “Good design” in favor of simple geometric figures, which now constitute the fundamental principle of his plastic expression.

The different parts of a piece of furniture are thus broken down into autonomous volumes, highlighted by a color, a material or a pattern, to which equal importance is given. These are then redistributed by playing scale ratios or repeated rhythmically. The color (red in the first place) promotes “greater sensory reading”, before the use of patterns (mainly the grid or the stripe) becomes recurrent; the vertical lines that he places on his furniture, symbols according to him of calm and serenity, act as signage. For the lacquer process, Sottsass substitutes a new printed laminate from Abet Laminatti which he applies to his famous Superbox cabinets and then to storage furniture. At the end of the 1970s, Ettore Sottsass definitively broke with functionalism. He joined Alchymia, then founded the Memphis group in 1981. Through its liberating and experimental vision of design, this movement, which favors the symbolic and emotional dimension of objects, confirms the bankruptcy of modern ideologies. Memphis has the effect of a bomb.