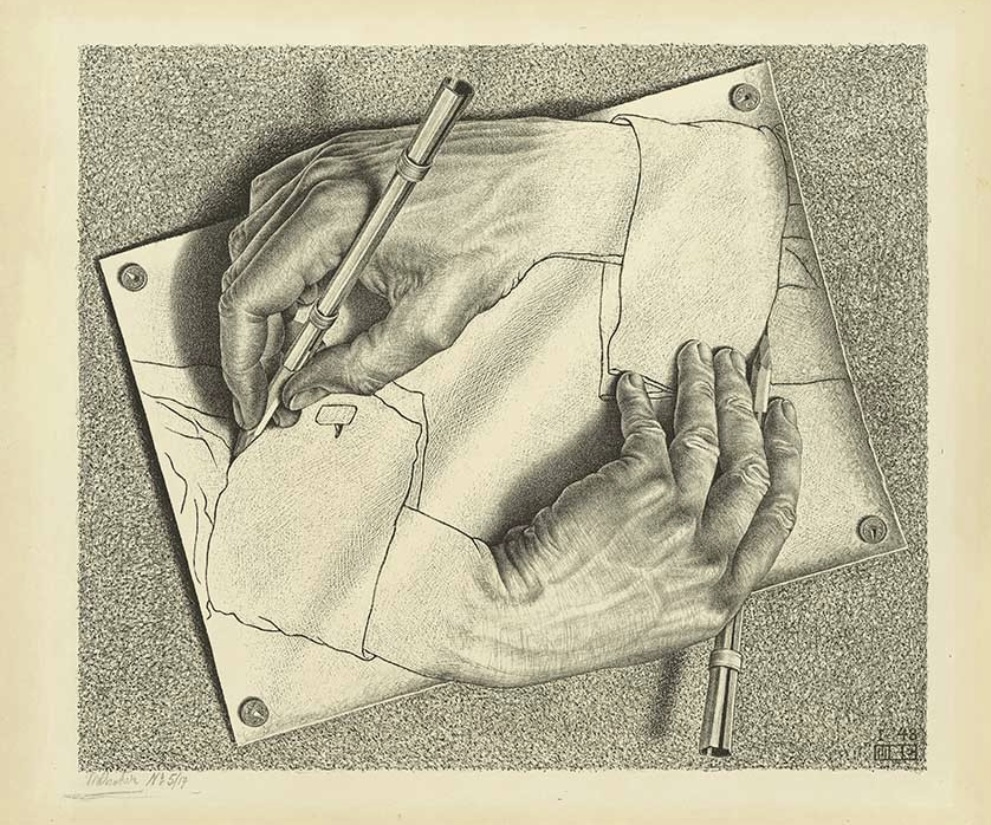

Maurits Cornelis Escher

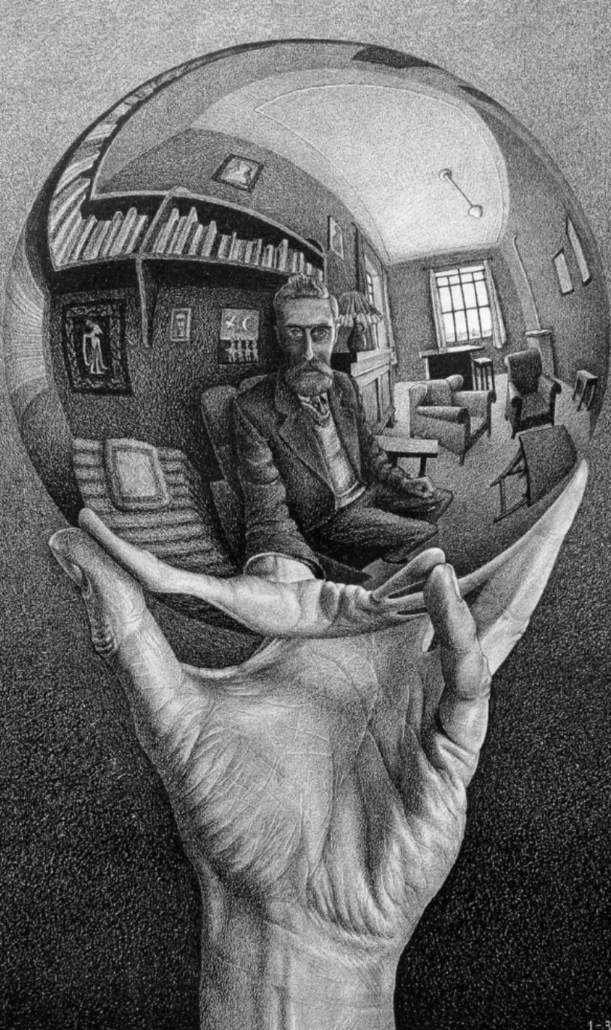

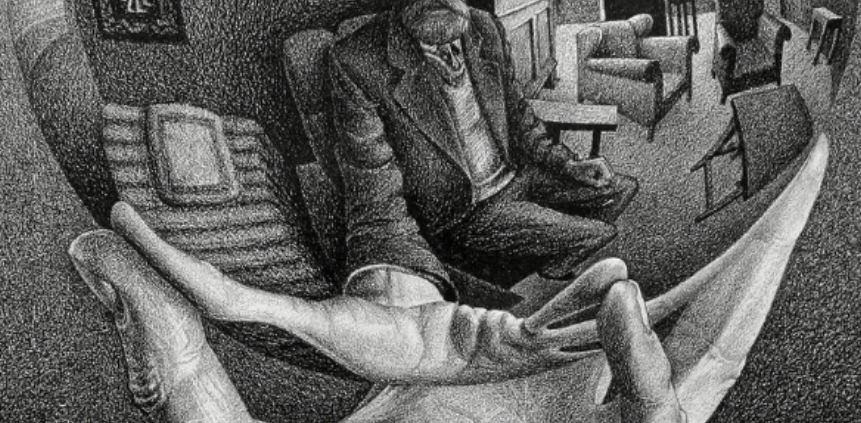

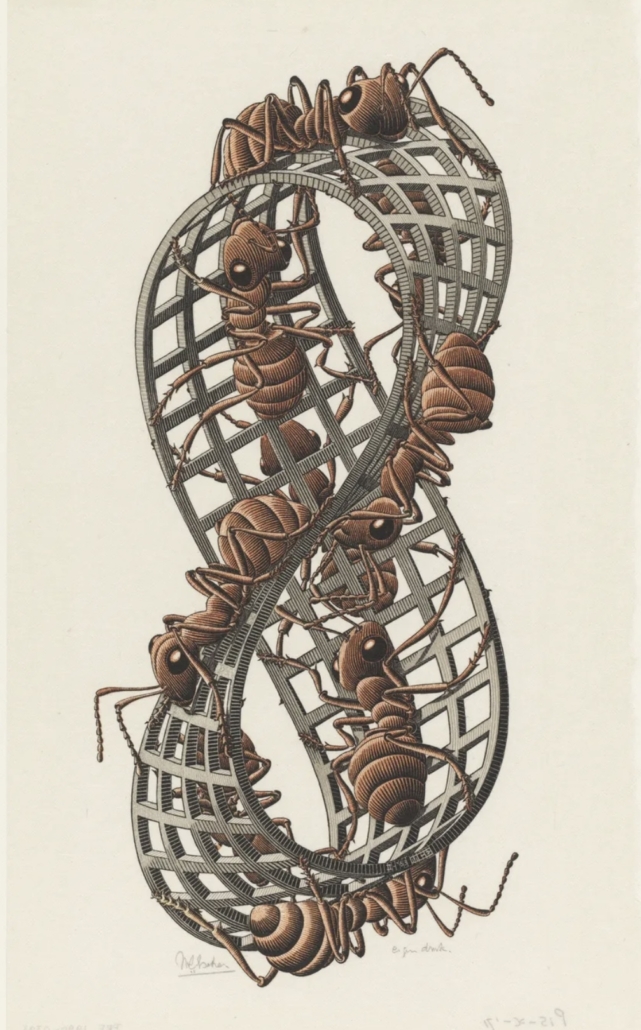

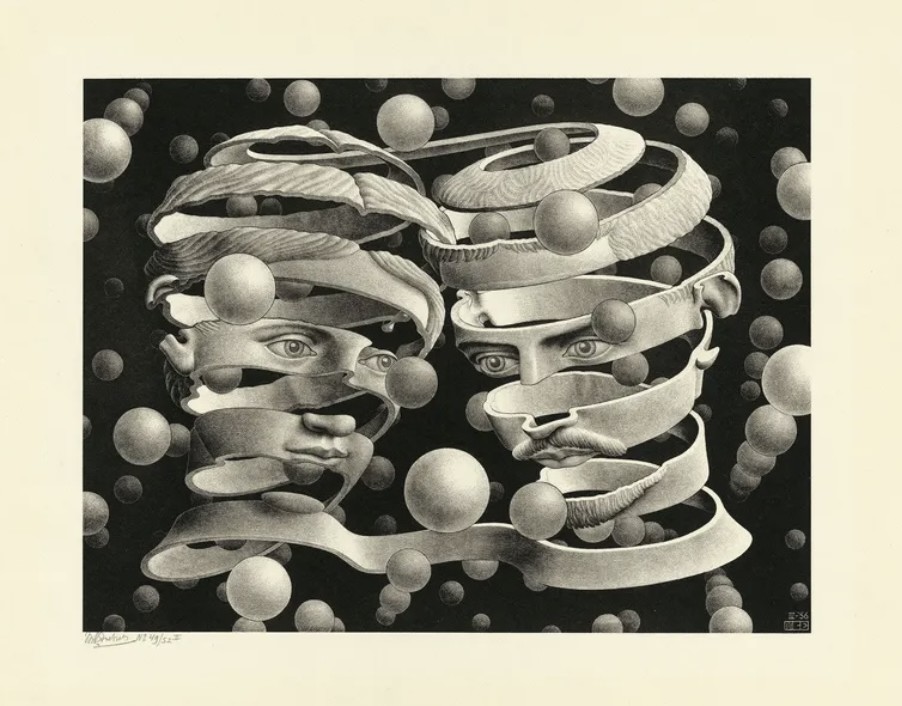

Maurits Cornelis Escher, or as he preferred to be called, M.C. Escher, is a fascinating artist who knew how to transform geometry and mathematics into art, through his tessellations, optical illusions and impossible worlds, but who was initially also a remarkable landscape painter.

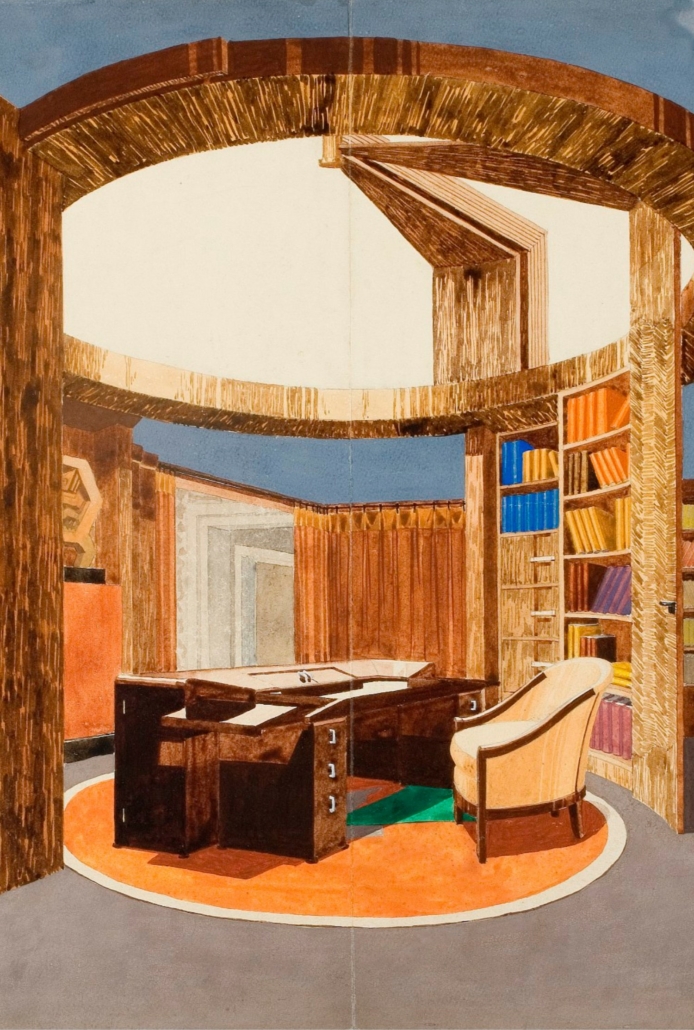

The exhibition, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin and Federico Giudiceandrea, two of the leading experts on the artist, immerses us in the imaginative and astonishing world of this Dutch genius, born in 1898 in Leeuwarden, Netherlands.

Celebrated for his visionary creations, visual paradoxes, and infinite geometries, he has become an icon over time, not only for mathematicians and researchers, but also for the general public, captivated by the visual and conceptual power of his work. His creations represent a true convergence of the scientific world and artistic creation, profoundly influencing the worlds of design, graphic arts, film, advertising, fashion, and music even today.

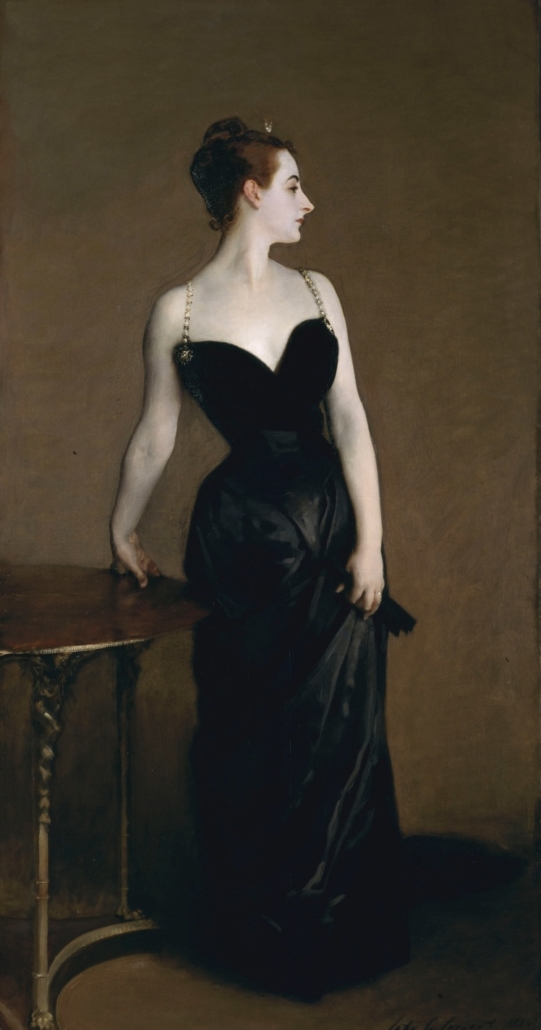

From the 1950s onward, his popularity steadily increased. Thanks also to his connections with the scientific and academic world, various journals began to dedicate articles and reviews to him. In the United States, the hippie movement appropriated his works, modifying and reproducing them on posters and T-shirts, in a psychedelic style.

The exhibition immerses us in his work and its progression toward abstraction, impossible perspectives, and astonishing, sometimes disconcerting, representations of seemingly plausible worlds irreconcilable with reality, which M.C. Escher managed to bring together in a unique artistic dimension.