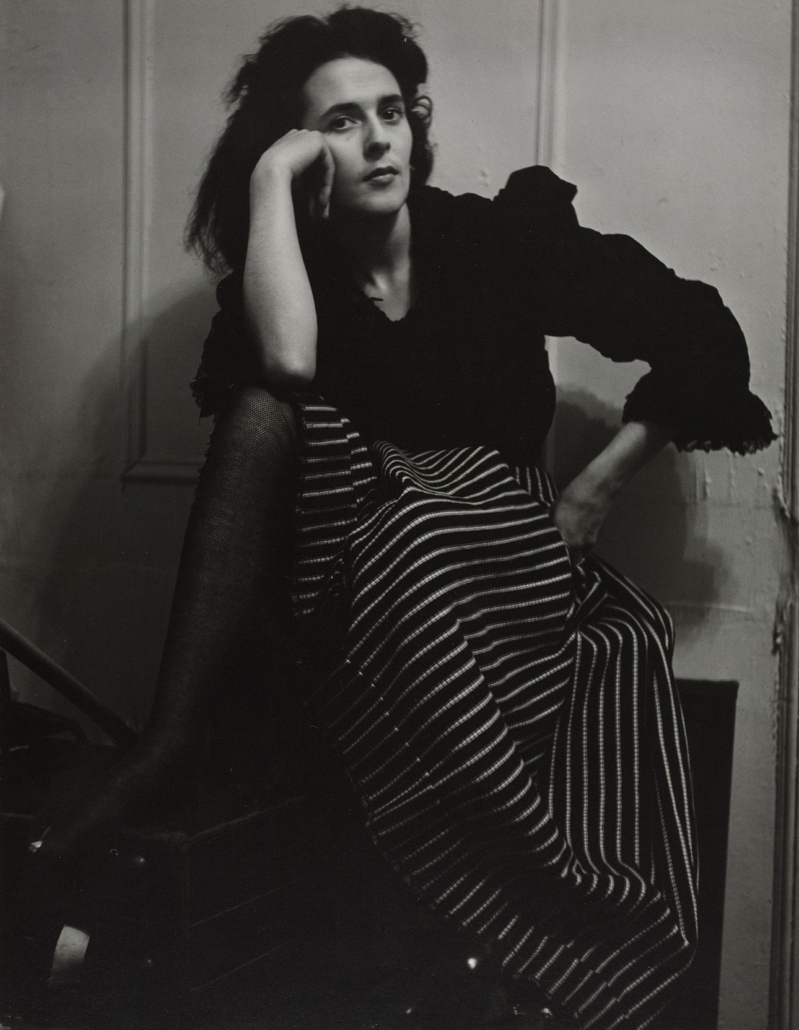

Leonora Carrington

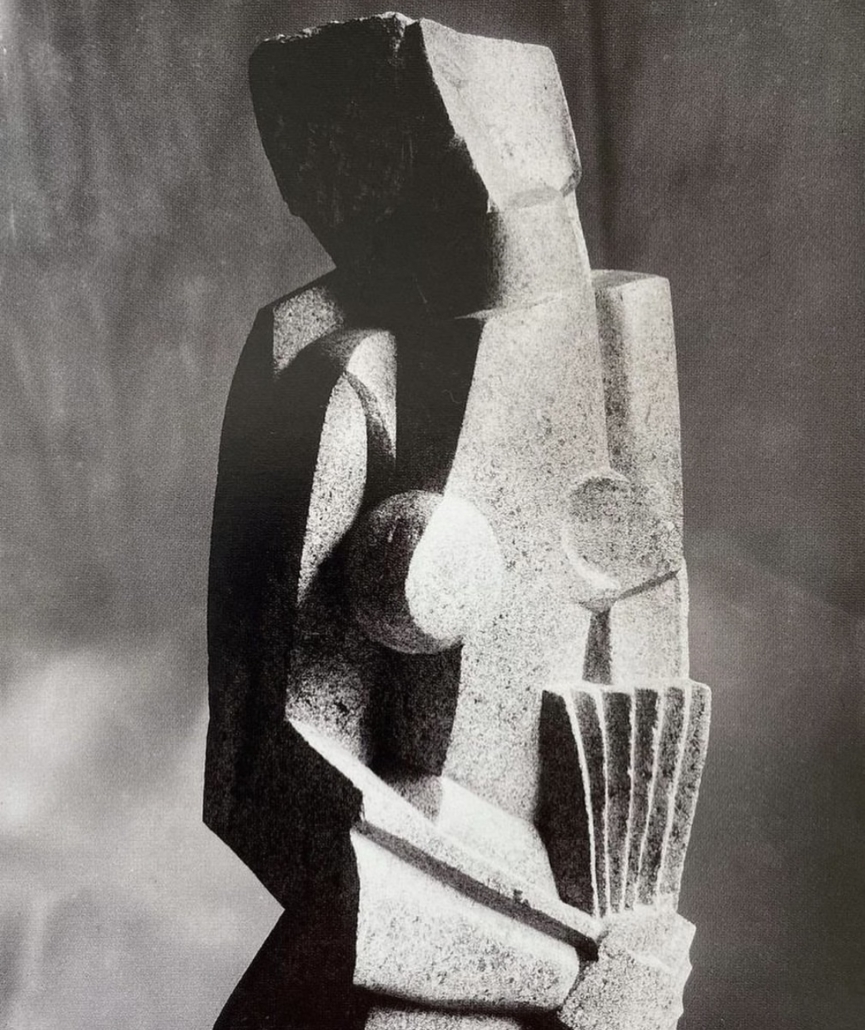

An artist, avant-garde feminist and environmentalist, woman, mother, migrant, survivor of mental illness, and constantly evolving spiritual seeker, Leonora Carrington left behind an extraordinary and radical legacy. Born in 1917 in Lancashire, England, Leonora Carrington forged her identity through travel, both internal and external. From Florence to Paris, from the South of France to Spain, and finally to Mexico where she became a cult figure, her exceptional journey fueled a body of work at the crossroads of surrealism, mythology, and esotericism.

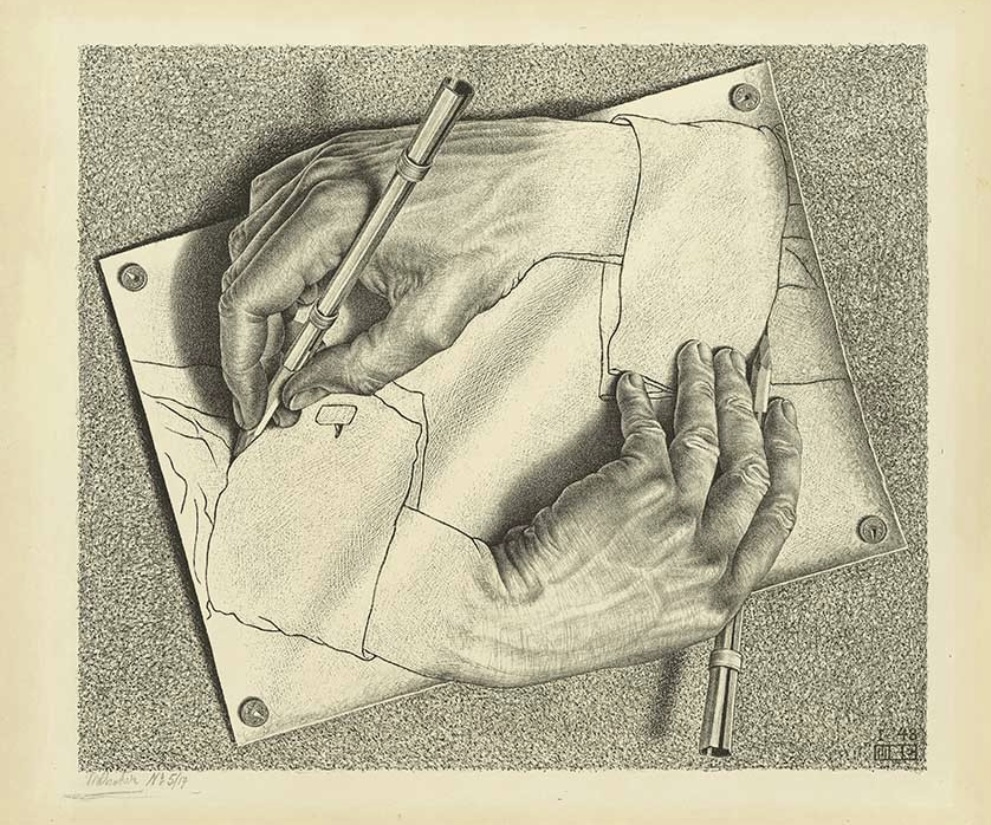

This exhibition, bringing together 126 works, is the first major one in France devoted solely to Carrington’s work. It presents Carrington as a “Vitruvian Woman”: a complete artist, representing a model of harmony and innovation. Her creations fuse human and animal, masculine and feminine, giving form to a world where metamorphoses and symbols resonate with one another.

Through a chronological and thematic approach, as well as a unique presentation of her diverse visionary creations, the exhibition explores the artist’s main themes and areas of interest: her discovery of classical Italian art in Florence during her adolescence, her fascination with the Renaissance, her Celtic and post-Victorian origins, and her involvement with Surrealism during her time in France. The exhibition thus highlights the exceptional legacy of this perpetual traveler, always in search of self-knowledge.